Make-a-Lisp in Elm

Recently I finished my second Make-a-Lisp (Mal) implementation. What is Mal you ask?

- Mal is a learning tool made by Joel Martin.

- Mal is a Clojure inspired Lisp interpreter.

- Mal is implemented in 68 languages (and counting).

Following the 11 step incremental process guide you’ll end up with your very own Lisp interpreter (which is powerful enough to be self-hosting). Along the way you learn a great deal about the programming language you’re implementing in. And, if you don’t know it yet, you discover the elegance and simplicity of Lisp.

My first Mal implementation was in Livescript (one of the many compile-to-JS languages). This time I wrote it in Elm, a purely functional strong statically typed language (also compiles to JS). I thought a second implementation would be easier. Boy was I wrong.

Why was it harder? This were the challenges:

- Running Elm from the command line.

- Mal expressions can have arbitrary side effects, Elm doesn’t do that.

- How to represent a mutable environment in Elm.

Elm command line program

Elm is a language for making web apps. It has a unique program structure that is well suited for this.

Using Platform.program you can create a headless Elm program. The program exposes three methods: init, update and subscriptions. Init does what you guess. I won’t go into subscriptions, look at the docs if you are interested. Update is the important function. Each time a message is received the update functions job is to compute the new state given the old state and the message.

In “normal” Elm web apps a message would be a mouse click, key press, or a received web socket message. For the REPL we need messages for two things: reading a line of input and writing a line of output. The basic loop looks like this:

update : Msg -> Model -> ( Model, Cmd Msg )

update msg model =

case msg of

LineRead line ->

let

(newModel, output) = eval (read line)

in

(newModel, writeLine output)

LineWritten ->

(model, readLine "prompt> ")

Note: all code here is simplified, for the real code have a look at the repo.

writeLine and readLine are “ports” to Javascript. Ports have border patrol which ensures that the values passed in or out are of the correct types.

port writeLine : String -> Cmd msg

port readLine : String -> Cmd msg

To bootstrap the REPL the following Javascript code is used. Notice how the writeLine port sends a lineWritten message back when the console.log is done.

var app = mod.Main.worker();

app.ports.writeLine.subscribe(function(line) {

console.log(line);

app.ports.lineWritten.send();

});

app.ports.readLine.subscribe(function(prompt) {

var line = readline.readline(prompt);

app.ports.lineRead.send(line);

});

Arbitrary side effects

Any Mal expression can have arbitrary side effects. They don’t have to be defined (statically typed) like in Elm. Let’s say we want to interpret the following Mal code:

(do

(println "test")

(+ 1 2))

The only way to perform a side effect in Elm is by passing a command (Cmd) out of the update function. So when the interpreter encounters the println function call it has to store it’s current execution context and return all the way up the call stack to the update function and return a writeLine command to the Elm runtime (writeLine is not a function, it is a value that instructs the runtime what side effect is wanted).

When writeLine is done it will send a lineWritten message back so that the interpreter can continue it’s execution. Using continuations the execution context is restored to the point right after the evaluation of the println expression.

Here is an example to illustrate how the continuations are used:

println line =

Eval.io (writeLine "test")

compute3 =

Eval.success (1 + 2)

-- Ignores result from println and returns 3.

println |> Eval.andThen (\_ -> compute3)

The magic is in Eval.andThen. If an evaluation returns a EvalIO, it is immediately returned. But, in the second argument a continuation call chain is build up, to be performed when then IO is done.

Eval.andThen f e =

case run e of

EvalOk val -> f val

EvalErr msg -> EvalErr msg

EvalIO io cont ->

EvalIO io (cont >> f)

Eval.elm is inspired by the parser combinator library elm-combine (by the way, the Reader is implemented with elm-combine). Eval is a monad that hides the complexity of passing the environment and handling and chaining the various results of each interpretation step (success, failure and IO).

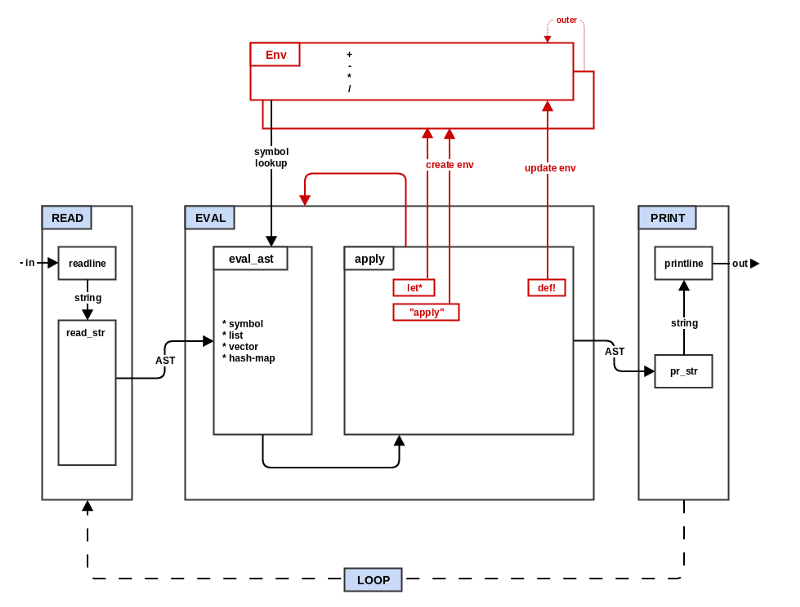

Mutable environment

Mal needs a mutable environment in step 3 of the process guide. Elm doesn’t do mutation. Now luckily a mutable environment can be simulated with a immutable environment. Each time a symbol is mutated, a copy of the environment is made but instead of copying the old value the new one is put in. This is what Elm’s core Dict does (it doesn’t exactly copy the whole old value but for this story lets assume it does).

So far so good. The hard part is dealing with the tiny arrow in the upper right corner, the one called “outer” linking from one environment to the other. Elm is a pure language. That means all functions are side effect free. In other words: all values are immutable and no references or pointers are allowed. But we do need a pointer from each environment to it’s outer.

I came up the following “solution” (the quotes because it is a dirty and error prone way of emulating pointers — do NOT try this at home). Each red box in the picture above is called a Frame, the total of all frames is called Env. Each frame is identified by an integer: a frameId. This frameId is then used as a “soft pointer”.

type alias Frame =

{ outerId : Maybe Int

, data : Dict String MalExpr

, ...

}

type alias Env =

{ currentFrameId : Int

, frames : Dict Int Frame

, ...

}

Eventually I got this scheme working. With it came the burden of bookkeeping which frames are used and which are not. Normally the garbage collector does this job, but since all frames are referenced from Env.frames it can’t do it’s job anymore.

Env.elm contains a (very simple) garbage collector and does reference counting on each frame to determine which frames can be freed. It took some cycles of testing and debugging to get this code right. Especially debugging the magical self-hosting of Mal was hard. Printing every evaluation and every change to the environment led to thousands of lines of debug log. Finding the spot where problem arose was not always clear because closures link back to frames created earlier.

Joel Martin pointed out that maybe the environment can be implemented in Javascript through the use of the JS interop. I think it can be done with Native modules. This would probably result in much much less code. Something to look at on a cold winter’s night…

Bottom line

Implementing an interpreter for a language with mutable values and arbitrary side effects in an implementation language which has none of those things is not straightforward.

Sometimes the more verbose implementations (especially for modern languages) indicate that a language is “non-Lispy” — Joel Martin

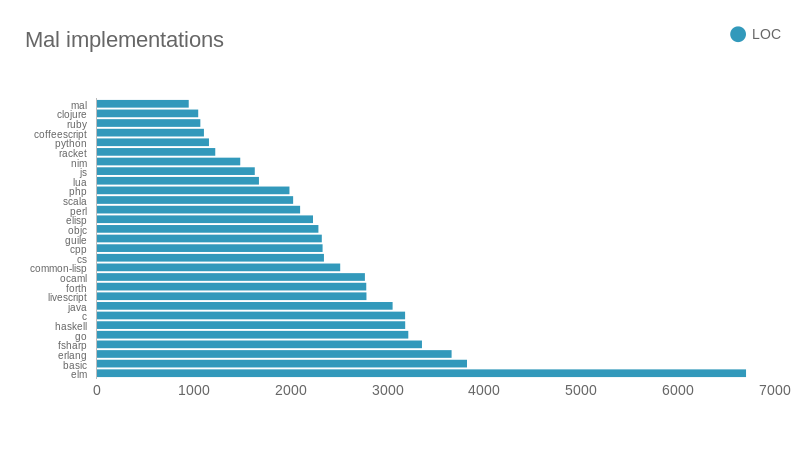

What are Lispy languages? Judging by the the LOC in some Mal implementations, the top ones are the more Lispy languages:

Elm has by far the most LOC. Although the comparing on LOC is not completely fair. I used elm-format to auto format the styling of all the source code. It results in a readable, consistent, but pretty verbose code style.

Even without elm-format the LOC would be bigger than the rest. Conclusion: Elm is not a Lispy language. What makes a language Lispy then? Looking at what the languages have in common that are Lispy and subtracting what Elm does not have, I would say:

- Dynamic typing

- Arbitrary side effects

- Mutable state

Elm was an excellent choice for the learning experience. It isn’t a very practical language for writing an interpreter. All in all it was a nice challenge.

On to the next language! Assembly maybe?